The 2014 Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura — three scientists who helped develop blue light-emitting diodes, or LEDs, in the early 1990s.

So why did the Nobel committee think LED lights are such a big deal? In part, they said, because of the technology's potential to change the world: "The LED lamp holds great promise for increasing the quality of life for over 1.5 billion people around the world who lack access to electricity grids: due to low power requirements it can be powered by cheap local solar power."

One big virtue of LEDs is that they're roughly 15 times more efficient than regular bulbs — and they keep improving at a remarkable clip. If they continue to get cheaper, they could replace fluorescents and incandescent lights in places like the United States and Europe, potentially cutting down on a major source of energy use and helping to tackle global warming (although it's also possible that, if lighting gets more efficient, we could just end up using more of it).

So how important are LEDs, really? Here's an overview:

A short history of LEDs

LEDs are often viewed as the next generation of lighting technology. First we had fire. Then gaslight in the 19th century. Then Thomas Edison developed his filament bulbs. More recently, we've had the fluorescent and compact fluorescent bulbs most people now have in their offices and homes.

Those innovations all helped us get more and more lighting with less and less energy. The cost of providing a given amount of light has dropped 3,000-fold since the early 1800s.

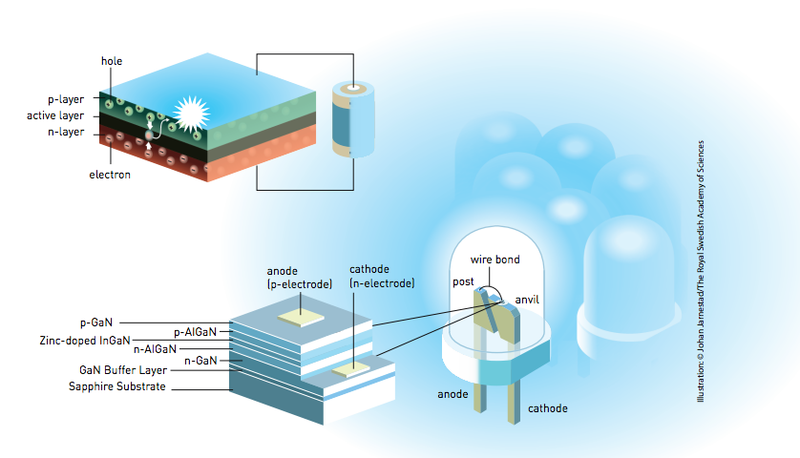

Now LEDs look more promising still, since they use less energy and don't contain harmful mercury, like fluorescent bulbs do. But it wasn't always obvious that LEDs would be the next step. Back in the 1980s, diodes could still only emit red or green light, which isn't very handy for lighting a room. But in the 1990s, Nakamura helped develop the first high-brightness blue LED — building on the work of Akasaki and Amano in Japan. Now it was conceivable that LEDs could be used for everyday purposes.

Since then, LEDs have advanced further and become used for an array of different sources. They're in streetlights and traffic lights. They're used for displays in computers and smartphones. But the big, idealistic hope is that they could help bring light to the 1.5 billion people who don't have it.

How LEDs could help light up the developing world

It's worth remembering that there are about 1.2 billion people in the world who still lack access to electricity. And many people who do have electricity barely have enough power for reliable lighting.

As a result, many households still burn either wood or gas for lighting. Not only is that inefficient, but the resulting indoor air pollution is killing millions and millions of people. Plus there are all sorts of knock-on effects — it's much harder for kids to study for school if they can't even read their books.

Now enter LEDs. One big thing these lights have going for them is efficiency. Incandescent lightbulbs are extremely inefficient — it takes a lot of energy to heat up the filament inside, and only a fraction (2 percent or so) of that energy is given off as light. LEDs do considerably better. Engineers can now get about 300 lumens of light from the most advanced LED bulbs for every Watt of electrical power used — compared to just 70 lumens from a compact fluorescent bulb and just 16 for a filament bulb.

In other words, LEDs are about 4 times as efficient as CFLs and 15 times as efficient as filament bulbs. As Charles Kenny explained in Foreign Policy, those low energy demands for LEDs mean that many households that aren't currently connected to the grid could use solar panels and small batteries to power LED lights.

The biggest obstacle is cost: LEDs often have a higher upfront price tag than other types of light bulbs. But that price has been steadily falling over time, to the point where we could start to see wider adoption in poorer countries. (The other advantages? LEDs last longer than compact fluorescent bulbs, they don't break as easily, and they don't contain mercury — so they're easier to dispose.)

Could LEDs help tackle global warming?

The other big potential application for LEDs is in the developed world. It's worth remembering that lighting is a massive source of energy use — it makes up about 17 percent of US electricity consumption.

In theory, LEDs could help change that. Most plans to boost energy efficiency and reduce greenhouse-gas emissions in the United States and Europe envision LEDs replacing all existing lighting technologies by 2050 or so. (See, for instance, this recent UN report on "deep decarbonization.")

The one hitch, however, is what's known as the "rebound effect." Historically, as lighting has gotten cheaper, we've used more and more of it — so that overall energy use for lighting has actually gone up, not down. That's one big consideration here. LEDs could well bolster lighting efficiency and leave us all better off. But it's not guaranteed that energy use — and greenhouse-gas emissions — will go down as a result.

Update: See also my colleague Tim Lee's post on the amazing efficiency progress that LEDs have made over the years. It includes this chart:

THE INVENTORS OF EFFICIENT BLUE LED'S..

SOURCE : a paper from the university of wisconsin

Thank You friends... FoR rEaDiNg My ArTiCle - Bharath Kumar Goud